"When it came time to approve Prozac, the combined efforts of the drug company and the FDA could not come up with even one good study that unequivocally supported the value of Prozac in comparison to placebo. The FDA then decided to break its own rules. It gave approval to Prozac based on its marginal effectiveness when in combination with addictive tranquilizing drugs that reduced the patients' Prozac- induced agitation, anxiety, and insomnia. In the end, Prozac was in reality approved as a combination drug-Prozac plus sedative, addictive tranquilizers, such as Valium and Dalmane. But the medical profession and the public were never told.”

- Peter Breggin, MD- The Antidepressant Fact Book (2001)

Many individuals experiencing depression and anxiety often notice improvements when taking antidepressant medications, such as SSRIs. This sentiment is shared by medical professionals describing their patients' outcomes. However, a major dilemma emerges when we consider the consistent discovery that the difference in effects between antidepressants and placebos is exceedingly minimal.

Let’s call it a dirty little secret.

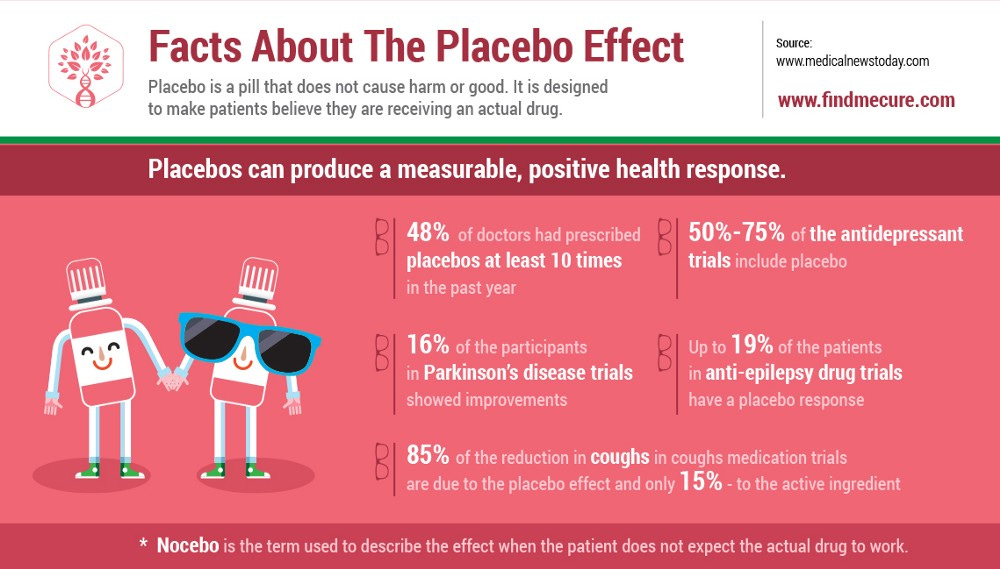

Despite the apparent equivalence in outcomes between drugs and placebos, both can produce substantial responses. In trials investigating drugs for depression and anxiety the placebo response falls somewhere between 30 and 50%.

Recent antidepressant clinical trials have seen a “placebo drift” in that the placebo response rate is higher than in trials conducted 30 years ago, with a slight lowering of the response to antidepressants and a substantial narrowing of the drug-placebo difference.

As I've emphasized before, when a drug fails to demonstrate superiority over a placebo, pharmaceutical companies often opt not to publish the data from that specific trial. Hence, any reported superiority of a drug over a placebo is likely inflated, given the selective publication of trial data by pharmaceutical companies.

In our medication-centric society, there is considerable academic discourse dedicated to debating whether a drug genuinely provides any clinically significant advantages over a placebo. This debate persists even in light of the noteworthy adverse reactions, side effects, and elevated rates of relapse associated with antidepressant drugs.

Antidepressant Drugs as an Enhanced Placebo Response

It becomes evident that any perceived benefit from an antidepressant drug is essentially an "enhanced placebo response." Placebo effects hinge on the perceptions and expectations embedded in individuals undergoing treatment, and these effects can be magnified or diminished based on factors influencing cognitive expectancies. In the case of SSRIs, being psychoactive substances that impact the brain, patients and doctors can reliably discern who has received the actual drug and who has been administered the placebo. This revelation casts doubt on the true double-blind nature of the trials.

Several studies consistently demonstrate that when patients are aware they are receiving a drug, their responsiveness to the treatment is notably higher compared to situations where they are uncertain about whether they are receiving the actual drug or a placebo. This has been the case in “antidepressant” drug trials.

In actual clinical practice, the act of labeling a drug as an "antidepressant" holds significant sway over the drug response. The very name carries a powerful suggestion that shapes patient expectations and, consequently, influences their subjective experiences with the medication.

Why Anecdotal Reports are Harmful

Let's run some quick calculations. With approximately 260 million adults in the United States, data from 2015-2018 indicates that 13.2% of adults aged 18 and over used antidepressant medications in the past 30 days. While it's reasonable to assume that the current figure is likely higher (estimates now are closer to 20%), let's take a conservative approach.

This equates to approximately 34 million individuals who have used an "antidepressant" drug in the past 30 days.

Assuming a modest 30% response rate to a placebo (though it's likely higher), this implies that at least 10 million individuals would report experiencing an antidepressant effect from a dummy pill.

When doctors confidently claim, "I believe antidepressants help some people because I have witnessed it in clinical practice," it exposes a critical gap in the evidence-based evaluation of mental health interventions.

Those people are experiencing a known placebo response!

Every day in the United States, we expose millions of adults to known adverse drug reactions, all in pursuit of a response that could have been achieved by prescribing a simple sugar pill.

Now, consider that we subject children to the same practice, where the known placebo response is even higher!

Natural Recovery

It's estimated that about half of all depressive episodes in adults will naturally resolve within a 6-month period. This highlights the transient nature of depression without formal treatment. In fact, I would argue that the majority of acute distress situations presented in primary care are episodic and typically resolve spontaneously as stressors diminish. Resilient individuals often adapt to the challenges they confront, representing the innate capacity for self-recovery in the face of adversity.

If doctors opted for nothing else but to offer support and encouragement, outcomes for depression would improve, and adverse reactions to drugs could be eliminated.

Considering the temporary nature of these episodes, it's common for individuals to attribute improvement to a drug, which may better align with the transient nature of emotional distress. Ethical and scientifically minded practitioners must actively guard against this fallacy when communicating improvements to patients.

Attributing improvement to a pharmaceutical intervention, when it's more directly related to coping mechanisms or necessary changes in response to a stressor, not only undermines resilience but also poses a risk of fostering drug dependency. Recognizing and reinforcing the role of resilience and adaptive coping strategies is essential to avoid potentially harmful dependencies on medication. Practitioners must be vigilant in differentiating between the effects of drugs and the inherent capacity for resilience in patients.

Simply acknowledging the temporary nature of distress and enhancing people's ability to respond to stress could prevent millions from unnecessary exposure to drug reactions and negative health effects. Emphasizing resilience-building strategies and coping mechanisms can be a more prudent and holistic approach to mental health, steering clear of potential pitfalls associated with unnecessary pharmaceutical interventions.

Harnessing the Placebo Response

Given the robust placebo response in mental health treatment, it's perplexing to me that individuals would dedicate their careers to advocating for a pharmaceutical when that drug offers no discernible clinical benefit over a placebo. The risks associated with psychiatric drugs are substantial, and medical professionals prescribing them bear a profound responsibility to comprehend and communicate these risks effectively to their patients.

To me, the placebo response isn't merely a benchmark for comparison in clinical trials; rather, it signifies a potential tool we could harness to aid patients in their natural healing or recovery. It reflects the remarkable power of the mind to influence both our health and our overall experience. Recognizing and understanding this innate capacity opens doors to exploring innovative approaches that leverage the mind's potential in promoting well-being and healing.

I believe that individuals who respond to either a psychiatric drug or a placebo pill often hold beliefs that there is something inherently wrong with them. This perception can lead them to believe that an external intervention, such as a medical treatment, is necessary to correct their ailment.

In my opinion, this represents the initial response in drug trials. In the long run, I see this as a problematic mindset, potentially contributing to the high relapse rates observed amongst those who turn to psychiatric drugs. Addressing the root of this belief system may be crucial in developing more sustainable and effective mental health interventions.

In upcoming articles, I plan to explore more deeply the specific factors contributing to the placebo response and investigate our innate capacity for self-healing, extending beyond mental health.

Yet, for the purposes of this article, let's identify some practical strategies to leverage the placebo response for enhancing mental health treatments, excluding the effects of psychotherapy. Implementing these practical strategies in primary care or in outpatient psychiatry could notably improve outcomes and, in turn, save lives.

Boost Expectations: Expectations play a crucial role as they embody the anticipation of a particular outcome, serving as a central mechanism for placebo effects. When communicating with clients, emphasizing that emotional challenges such as depression and anxiety are temporary and valid reactions to problems that can be faced and resolved, coupled with expressing belief in their capacity to tackle these issues, will dramatically enhance treatment outcomes.

Don’t Communicate Depression & Anxiety as a Disease: When presenting depressed mood and anxiety as a disease, it alters how an individual interprets their experience. Framing these conditions as disorders can evoke a mindset that suggests a medical solution to “fix” what is broken. Labeling thoughts and emotions as “disordered”, or symptoms of an illness, will lead people to perceive themselves as inherently flawed. This externalizes the struggle to forces outside their control. Conversely, validating their experiences as normal reactions to adverse & improving their reactions to such events can increase their willingness to make necessary changes. Enhancing efficacy is crucial in any mental health treatment.

Prescribe New Behaviors: In reality, these behaviors themselves embody antidepressant qualities. However, the act of actively engaging in these behaviors with the belief that they will contribute to improvement constitutes a practical strategy. Activities such as early morning sun exposure, moderate exercise, gratitude journaling, meditation, and prayer have demonstrated efficacy in enhancing mood. Yet, I am inclined to believe that the impact of these behaviors would be limited unless the individual truly believes in their potential efficacy. If the practitioner effectively communicates the antidepressant effects of these behaviors and prescribes their daily practice, it can significantly enhance the individual's expectations and, consequently, their overall experience.

Advocate for Nutritional Interventions: This suggestion aligns with interventions that truly exhibit antidepressant effects, and the influence is likely to be amplified by belief. Recognizing that enhancing physical health contributes to improved mental well-being is well-established. Additionally, nutrient deficiencies and metabolic conditions can significantly impact anxiety and mood. Modifying one's diet with the belief that it positively affects mood is likely to result in mood improvement, regardless of whether the food itself is the actual mechanism of action.

Be Kind and Supportive: Practitioner characteristics, like empathy, friendliness, and competence, favor the formation of positive expectancies. Caring and warm patient–practitioner interactions can enhance the therapeutic value of clinical encounters when patients’ positive expectancies are actively encouraged and engaged. A patient-centered approach rooted in demonstrating care and empathy can positively enhance a patient’s experience within the clinical environment and activate psychosociobiological adaptations associated with the placebo phenomenon.

It is abundantly clear to me that current practices in the mental health field are causing harm, with unmistakable and observable outcomes. The adverse effects of commonly prescribed psychiatric drugs and the harmful ideology surrounding mental illness are so significant that, unless we initiate a course correction immediately, we are likely to witness a continued deterioration of our society.

When people seek solutions, the first crucial step is to promptly halt practices that have been proven to be harmful. Taking it a step further, let's leverage scientific findings to construct an environment where individuals can safely heal, fostering a supportive atmosphere for necessary changes. Acknowledging the need for broader cultural shifts, including addressing issues such as abuse, neglect, poverty, and war, which contribute to poor mental health, is of course necessary. However, until these societal challenges are fully eradicated, let's critically examine how our healthcare system responds to those who are suffering and implement constructive changes.

Wonderful article! Nice to see the quote from Dr. Breggin. Dr. Breggin is one of those rare psychiatrists who so beautifully uses these practical strategies like boosting expectations and giving full support, for successful outcomes. His writings and videos should be required material for all in the field.

In my experience with my husband, anti-depressant drugs do seem to lessen the intense feelings but they do nothing for the long-term treatment of depression. I have attributed this to the numbing effect they have on all emotions. I think they make him less sad/depressed/anxious but also less joyful and less empathetic & compassionate. Do you think this is accurate or is the decrease in sadness/anxiety purely a placebo effect?