The Alarming Surge in ADHD Diagnoses

How misrepresented science & pharmaceutical influence has created an epidemic

Uncovering what has lead to the startling rise in ADHD diagnoses required a rigorous fact-finding mission on my part. I did not anticipate it would be this difficult. Securing reliable prevalence rates, especially pre-1990s, proved challenging amidst the convergence of psychiatry and pharmaceutical interests.

This era birthed the narrative of ADHD as a neurological condition, implying untreated ADHD could lead to lifelong impairments—driving home the urgency for medication intervention.

Eventually, I stumbled upon data presented at the 130th Annual American Pharmacists Association Conference in 2002. Their comprehensive documentation of the surge in ADHD diagnoses drew from various sources, including reports and hearings held by the Department of Education, Drug Enforcement Administration, as well as public survey data and reports from the Food & Drug Administration. Additionally, data was gathered from extensive searches across Lexis-Nexis, Infotrac, and ProQuest databases, scouring newspaper articles, magazines, and academic journals focused on ADHD and psychostimulants.

The results were shocking.

This provides some idea of how the diagnosis has been manufactured and sold to us throughout the 1990’s. What was once a rare and controversial label applied to the most severely disruptive boys has become commonplace.

ADHD Diagnoses 1985-2000

1985- 650,000 - 750,000 individuals diagnosed with ADHD

1990- 850,000 - 950,000 individual diagnosed with ADHD

2000- 4 to 5 million individuals mostly school-age children diagnosed with ADHD, 75-85% of whom were treated with psychostimulants.

Wow! I am not great at math… but that’s a substantial increase.

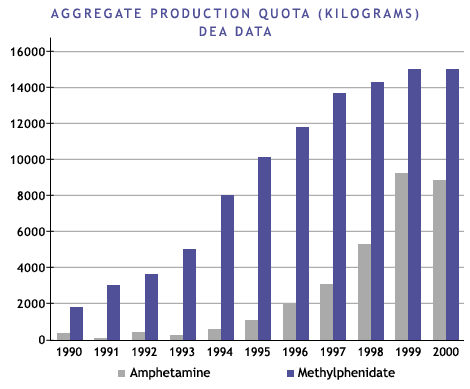

The image below reflects the production of stimulant drugs from 1990-2000. Big business!

Source: http://www.dea.gov/pubs/cngrtest/ct051600.htm

What Happened in the 1990’s?

The dramatic rise in the diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) coincided with a two-decade campaign by drug companies, aimed at doctors, educators and parents, to promote pills to treat the “disorder”.

The symbiotic relationship between pharmaceutical giants and academic psychiatry and psychology played a pivotal role in legitimizing ADHD as a brain condition and promoting pharmaceuticals as the solution. Beginning in the 1990s, there emerged a concerted effort to frame ADHD as a neurobiological disorder, fostering the narrative that it necessitated pharmacological intervention for effective management.

This narrative was bolstered by collaborations between pharmaceutical companies and influential figures within academic psychiatry and psychology, who received funding, research grants, and other incentives to conduct studies, publish papers, and deliver lectures promoting the use of psychostimulant medications.

As a result, ADHD diagnosis rates surged, with pharmaceutical solutions like Adderall and Ritalin becoming synonymous with ADHD treatment, despite ongoing debates about overdiagnosis and the long-term effects of such medications on individuals, particularly children.

Drug company marketing portrays ADHD as including relatively normal behavior, such as carelessness and impatience, and has exaggerated the medications’ benefits. As a result, the Food and Drug Administration has cited every major ADHD drug, including Adderall, Concerta, Focalin, Vyvanse, Intuniv and Strattera, for false and misleading advertising since 2000.

To this day, scientists debate whether the disorder is a form of biological dysfunction or simply a medicalization of normal deviance, promoted by pharmaceutical companies to sell drugs to bigger and bigger populations.

Data misrepresentations are frequent in the scientific literature dealing with ADHD and contribute to the appearance of misleading conclusions in the media.

Misrepresentation of Science to the Media

Data misrepresentations are pervasive in the scientific literature concerning ADHD, often leading to the dissemination of misleading conclusions in the media. When coupled with citation distortions and publication biases, these misrepresentations not only shape social perceptions but also skew scientific evidence, reinforcing the notion that ADHD is predominantly driven by biological factors. This synergy between misrepresentation, bias, and media influence not only distorts public understanding but also poses significant challenges in accurately assessing the multifaceted nature of peoples struggles with attention and focus.

A 2011 Pubmed article emphasized how misrepresentations of neuroscience data contribute to the propagation of misleading conclusions in the media regarding ADHD.

In their analysis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), researchers identified three types of misrepresentation. The first type revolves around significant disparities between study results and the conclusions drawn from them. This misrepresentation was evident in two scientific reports on ADHD. Surprisingly, only one of the 61 media articles that referenced both studies accurately portrayed the findings and, consequently, raised doubts about the conclusions drawn from them.

The second misrepresentation type involves firmly stating a conclusion in the summary while crucial data that significantly undermine the claim are relegated to the results section. To quantify this distortion, researchers examined the summaries of all articles asserting an association between polymorphisms of the gene coding for the D4 dopaminergic receptor and ADHD. Shockingly, only 25 out of 159 summaries acknowledged that this association confers only a small risk. This distortion is prevalent in the majority of media articles covering ADHD and the D4 gene.

The third misrepresentation consists in extrapolating basic and pre-clinical findings to new therapeutic prospects in inappropriate ways.

Junk Science

Despite widespread misrepresentation of scientific findings, ADHD brain imaging studies have not uncovered any specific or characteristic abnormality. The picture that emerges is of consistently inconsistent findings, which are statistical deviations (the brains would not be recognized by radiologists as being clinically abnormal), come from small sample size studies, don’t always accurately match for age and typically don’t control for IQ level, or for the possible effects of drugs prescribed.

In 2017, The Lancet Psychiatry published a study that the authors claimed provided definitive evidence that young people with ADHD have different and smaller brains compared to their healthy peers. In total they had data from the brain scans of 1713 patients diagnosed with ADHD and 1529 individuals who did not have this diagnosis, gathered from 23 research teams around the world.

Using certain measures of statistical variance enables them to make this claim on differences that are so tiny they are of no clinical relevance. This method enables them to hide the consistently inconsistent findings.

This mega-analysis thus makes the claim that children with ADHD have a smaller nucleus accumbens (NA) than non-ADHD children. However, if you look at the data by site you find 10 sites that found an average smaller NA in the ADHD group, 4 sites that found an average larger NA in the ADHD group, and 6 sites that found no difference.

Other studies did not control for IQ differences where associations between brain volume and IQ have been shown across a range of studies with adults and children.

How Many People Have ADHD Now?

According to a recent Forbes article with data cited from the Centers for disease control:

An estimated 265,000 U.S. children ages 3 to 5 years have been diagnosed with ADHD.

An estimated 2.4 million U.S. children ages 6 to 11 years have been diagnosed with ADHD

An estimated 3.3 million U.S. children ages 12 to 17 years have been diagnosed with ADHD.

Approximately 129 million children and adolescents worldwide between the ages of 5 to 19 years old have ADHD.

More than 366 million adults worldwide have ADHD as of 2020.

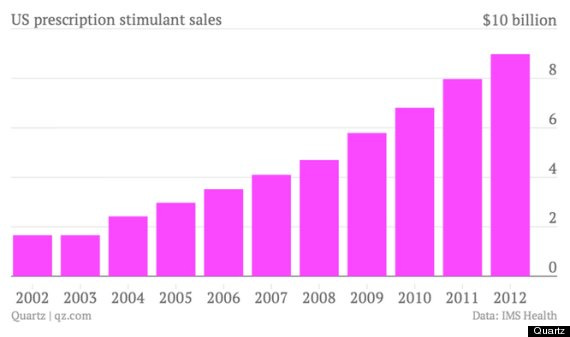

Between 2002 and 2012 alone their was a 400% increase in stimulant sales

Overall, stimulant prescriptions increased an additional 70% from 2011 to 2021.

The Brain is Likely Working as Designed

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain's ability to change and reorganize its structure, function, and connections in response to experiences, learning, and environmental stimuli. It is the brain's remarkable capacity to adapt and modify its neural pathways, synapses, and networks in order to optimize its performance and accommodate new information.

Neuroplasticity plays a crucial role in learning, memory formation, recovery from brain injuries, and the development of new skills. It allows the brain to reshape itself throughout life, constantly adapting and rewiring in response to various stimuli and experiences.

In the modern technological age, our focus and attention are under constant siege. The proliferation of digital devices, social media platforms, and endless streams of information has created a landscape of perpetual distraction.

The allure of instant notifications, endless scrolling, and the constant need for connectivity has reshaped the way we engage with the world around us. However, this is not indicative of a medical disorder but rather a reflection of our brain's natural design.

The incessant bombardment of stimuli and the addictive allure of technology have reshaped our cognitive patterns, resulting in reduced attentional capacity for non-stimulating activities.

The Problem with Stimulant Drugs

Stimulant drugs may provide an instant boost in attention and focus for many who take them, not just those diagnosed with ADHD. Whether it's cramming for exams, meeting tight deadlines, or simply striving for peak performance, the allure of heightened cognitive function is undeniable. This would occur if we used cocaine as well.

Methylphenidate (Ritalin) and amphetamines (Adderall) are the go-to prescriptions for ADHD, but their potential to turn ordinary individuals into super-focused achievers has sparked widespread interest for those without any clinical diagnosis.

However, the short-term benefits of these drugs come with a catch. While they may momentarily sharpen concentration and productivity, the long-term consequences and ethical implications of widespread stimulant use are problematic at best.

Prolonged use of stimulant drugs like methylphenidate (Ritalin) and amphetamines (Adderall) lead to tolerance, meaning higher doses are needed to achieve the same effects, escalating the risk of dependence and abuse.

Additionally, there are lingering uncertainties about the impact of stimulant use on brain development, particularly in children and adolescents. You would believe in a just society that was child centered we would be concerned about the long term risks of drugs used on children. Concerns also extend to possible cardiovascular effects and psychiatric complications.

In fact, kids who received the diagnosis of ADHD were 2.53 times more likely to harm themselves than kids who had the same level of ADHD symptoms but did not receive the diagnosis.

The most well-regarded and highly cited study of childhood ADHD, the NIMH’s MTA study, found that, by the six-to-eight-year follow-up, those who received medication did no better than those who did not. Moreover, none of the treatments had been successful by that follow-up: the children who received treatment still scored worse than the normative comparison group on 91% of the measures they tested.

Stimulant drugs like Adderall and Ritalin do not actually improve children's academic performance and may even increase the likelihood of children dropping out of school;

Proponents of ADHD diagnosis and treatment argue that untreated ADHD negatively impacts kids’ lives. They suggest that treating ADHD symptoms can improve kids’ lives. However, previous research has not found such an effect. Instead, research has found that:

Stimulant drugs like Adderall and Ritalin don’t actually improve kids’ academic performance and may even increase the likelihood of kids dropping out of school;

Ritalin leads to an 18-fold increase in depression, which decreases back to baseline when kids stop taking the drug;

Stimulants stunt growth and then rapidly lead to obesity; and

Stimulants may lead to hallucinations and other psychotic experiences.

The escalating risk of drug dependence, a staggering 18-fold increase in depression rates, and a host of other adverse reactions associated with long-term usage paint a bleak picture: the ADHD diagnosis and its prescribed medications serve as a gateway into the mental health system. What begins as an ADHD diagnosis too frequently spirals into a cycle of additional psychiatric diagnoses, each serving to justify the prescription of more pharmaceuticals by psychiatrists.

Screen Time, Social Media & Self Diagnosis

ADHD content on social media only added to concerns about over-diagnosis. Some startups offering remote ADHD care advertised their services on platforms like TikTok, adding to a chorus of social media posts (many misleading, according to one 2022 study) about common signs of ADHD, such as forgetfulness and difficulty focusing.

Generally speaking people are reporting 8 hours or more per day of cell phone use predominately texting, SnapChat, scrolling TikTok, Instagram, and watching videos.

Since more than 2 hours of daily screen time is associated with a myriad of adverse consequences what is happening to people on their phone 8-12 hours per day? Findings have linked overall screen time to depression and suicidal behavior among adolescents

Children in 2011 were estimated to sleep, on average, one hour less per night when compared with children of the early 20th century. It’s likely much worse now. It appears that adolescent girls, on average, are sleeping approximately 2 hours less than recommended.

The Common Sense Media report surveyed 1,000 parents and their children and states that 68% of teens bring their devices into bed, and nearly third fall asleep with their phones still there.

And many are not staying asleep either. The study found that 36% of teens wake up and check their mobile device at least once a night for a reason other than checking the time. Of those teens, a little more than half say it's because they received a notification or they just wanted to look at social media.

We're essentially cultivating a generation of phone-addicted teens and young adults who suffer from sleep deprivation. They're bombarded by relentless media campaigns promoting the ADHD narrative to rationalize struggles with focusing on less stimulating activities like reading, listening, and schoolwork. This trend pathologizes ordinary facets of human attention such as carelessness, boredom, and forgetfulness. Consequently, more individuals are likely to attribute their cognitive challenges to a fabricated brain disorder, exacerbating the perceived prevalence of ADHD.

The diagnosis of ADHD has unfortunately lost much of its value in today's society. While the original intent may have been to shed light on a small minority of children who faced challenges in adapting to the classroom environment, its implications have become distorted over time. The role of the pharmaceutical industry in shaping this narrative is clear. More diagnoses of ADHD, more customers.

In certain circles, ADHD has transformed into more than just a medical condition; it has become a personal identity and a way for individuals to present themselves to the world. For some, ADHD has become a defining characteristic that shapes their sense of self and influences how they perceive their place in society. There is concerning rise in ADHD coaches, ADHD social media influences and internet sites where you can quickly self diagnose and order drugs.

It's up to us to stop the madness and restore sanity.

Resist

No more bystanders

My son is on methylphyndate and quanfacine for fasd and I really don't see any benefit of them. So far though the side effect is absolutely zero appetite. I and he would like to be off the meds. So far my wife thinks they help and the psychiatrist is slowly increasing them with no fixes in his attention issues

I was diagnosed with ADHD in third grade and medicated though grade school. I continued to struggle with symptoms as an adult but I was not interested in going back on medication as my side effects from the meds had been so wholly miserable. ADHD was however, part of my identity, I was ADHD. I happened to visit a functional medicine doctor for another issue and he identified some pretty significant mineral and nutrient deficiencies. I took care of those as part of my treatment plan and it was almost scary how much my symptomology improved for ADHD. I no longer feel it is appropriate to label myself as someone who IS ADHD. My idea of what ADHD is, what causes it, and what it means totally changed. To me now it is a set of symptoms with a root cause. That root cause can be different things for different people, but it does not make sense to me anymore to think of it as some immutable part of who a person is. It frustrates me that I had gone so long and had to endure side effects like loss of appetite, feeling like I was buzzing, out of body like experiences all while on meds, when nutrition seemed to be the primary driver of my issues! The biggest frustration I have now when I try and talk to people about this experience is being told that clearly I NEVER actually had REAL ADHD and I had been misdiagnosed! Excuse me? Sounds like a no true Scotsman attack!