Despite the alarming warnings of increased suicidal ideation, glaring gaps in evidence, and undeniable risks, the rampant surge in antidepressant prescriptions for children and adolescents continues unabated. Astonishingly, the figures reveal a distressing upward trajectory: a staggering 41% surge in antidepressant usage among teenagers aged 13-19 in the 4 years prior to the pandemic. Post-pandemic the problem has worsened exponentially in the tumultuous years since 2020-2021, witnessing a jaw-dropping 12.6% year-on-year surge, a stark contrast to the already alarming average annual increase of 7.8% witnessed previously. The question looms ominously: have we abandoned caution in favor of convenience, disregarding the potential consequences on our vulnerable youth?

A startling reality emerges when we examine the landscape of antidepressant prescriptions: at least 80% of these potentially dangerous drugs are being prescribed by medical professionals in primary care settings, lacking the necessary training and expertise to effectively address mental health concerns. Pediatricians, burdened by time constraints, find themselves at a heightened risk of pathologizing normal childhood reactions and succumbing to the pressures of overdiagnosing clinical depression. What's more troubling is that these diagnoses often rely on biased screening measures, conveniently developed by the very pharmaceutical industry that profits from the sale of these drugs.

Don’t Accept “Depression Screening” Measures

The American Academy of Pediatrics has brazenly recommended an audacious strategy: subjecting adolescents aged 12 years and older to annual screenings for depression, using formal self-report tools on paper or electronically. These guidelines, undoubtedly, serve one sinister purpose: to inflate the number of children diagnosed with depression. It is a well-known fact that screening measures are notorious for producing false positives. This means that a substantial percentage of individuals identified through these screenings do not actually suffer from the supposed problem being screened.

According to psychologist Chuck Ruby, as stated in his book "Smoke and Mirrors," with approximately 74 million children under the age of 18 residing in the United States, subjecting them all to an 80% accurate screening tool would result in millions being falsely labeled. These guidelines not only perpetuate a dangerous cycle of overdiagnosis but also push countless innocent young individuals into unnecessary treatment-psychiatric drugs.

The ease with which normal developmental behaviors can be misdiagnosed as symptoms of clinical depression is a concerning issue. The primary screening measure utilized for assessing adolescent depression is the PHQ-9 for Adolescents, a self-report questionnaire comprising of nine questions that focus on supposed “depressive symptoms”. What is particularly noteworthy is the origin of this questionnaire—it was developed by none other than…Pfizer!

Now, let's take a closer look at these nine questions, shedding light on the potential for misinterpretation and misdiagnosis.

The ease with which pre-teens and teenagers can be labeled with moderate to severe depression is a matter of concern. Consider the timeframe involved - just a mere two weeks. Within this short duration, young individuals may face a multitude of normal adversities such as breakups, being grounded, being cut from a sports team, or struggling in school. It is crucial to acknowledge the wide range of typical life events experienced during childhood and adolescence and how one might naturally react within a two-week period.

Furthermore, let's examine the deliberate vagueness of the questions and the exclusion of contextual information. Adolescents are expected to determine the frequency of these "symptoms" on a scale ranging from "Not at all" (0 points) to "Nearly every day" (3 points). By design, this assessment tool fails to capture the nuances and contextual factors that contribute to emotional experiences. Consequently, if a teenager responds truthfully as a typical teen would, they are likely to screen positive for depression.

In an era where obtaining a clinical depression label and receiving a prescription for antidepressant drugs seems increasingly effortless, it is imperative to scrutinize each question and rigorously assess the validity of this screening measure to show parents how easy it has become to be labeled with clinical depression. The stakes are high, and we must question whether this approach truly captures the complexity of mental health or if it simply perpetuates a system prone to overdiagnosis and overmedication. Let us delve into each question to prove a very important point…who in the world would take this screening measure seriously?

The first question of the PHQ-9 for Adolescents, regarding "little interest or pleasure in doing things," suffers from a distressing lack of clarity in its definition. What exactly do they mean by "things"? Are they referring to mundane daily tasks, academic responsibilities, hobbies, or even specific activities like English class, cleaning up their room, or doing homework? This intentional ambiguity is not only baffling but also opens the door for misinterpretation. It comes as no surprise that a significant number of teenagers would hastily circle a 3, indicating a lack of interest or pleasure in various daily tasks. How can we accept such a poorly constructed question as a valid measure for assessing clinical depression?

Question #2 raises significant concerns with its lack of clarity and lumping together of different emotional experiences. It asks whether the individual is "feeling down, depressed, irritable, or hopeless." The problem here is the ambiguity of terms. What does "down" really mean? Is it simply feeling sad for a brief period? And how does it differ from being "depressed"? Additionally, including "irritable" and "hopeless" in the same question seems misguided. While irritability is a common occurrence among teenagers, it is entirely different from experiencing depression or hopelessness.

By merging these distinct emotional states, the questionnaire runs the risk of pushing typical teenage emotional reactions into the realm of pathology. It can inadvertently encourage young individuals to misrepresent normal emotional fluctuations as indicators of depression… and now it does. Just feeling irritable? Regardless of cause it is now an indicator of a severe psychiatric condition.

Question #3 aims to assess sleep-related issues. It is important to note that experiencing difficulties with sleep does not automatically indicate a symptom of clinical depression. In fact, most sleep problems have no direct correlation with depression.

Now, let's delve into the question itself: "trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or sleeping too much." First, it poses the perplexing inquiry of what "sleeping too much" means. How can we expect teenagers to accurately determine what constitutes excessive sleep?

Furthermore, the question fails to consider important contextual factors that heavily influence sleep patterns. For instance, whether a teenager has trouble falling asleep may depend on external factors such as the time they are asked to go to bed by their parents or whether they had taken a nap earlier that day.

These considerations shed light on the significant limitations and potential pitfalls of relying on vague and contextually ambiguous questions to assess sleep difficulties in adolescents. What is truly concerning is that, after answering just three questions, it becomes quite outrageous to think that a typical teenager may already have a score of 9, placing them on the threshold of being considered "Moderately Depressed."

Question #4 of the PHQ-9 for Adolescents asks, "feeling tired or having little energy?" This question seems almost absurd. How many teenagers do we know who don't express feeling tired or lacking energy on a regular basis? It's a common sentiment among adolescents dealing with the demands of school, extracurricular activities, and social pressures. We can't help but shake our heads in disbelief at the inclusion of such a seemingly trivial question in the assessment.

Considering the cumulative effect of these questions, it becomes increasingly disconcerting. If we keep score, how many teenagers would now have a total score that equals 12? It's quite remarkable to think that a significant number of adolescents, who may be experiencing the normal ups and downs of teenage life, would be classified as having a moderate level of depression based on this scoring system.

Question #5 addresses appetite and inquires about "poor appetite, weight loss, or overeating." Once again, we encounter concerns regarding construct validity, as appetite, weight loss, or overeating may have little to do with depression in most cases.

Furthermore, the question fails to provide clear criteria for evaluation. How much weight loss is considered significant enough to raise concern? Should weight loss even be considered a symptom, particularly when considering individual variations in body weight and composition? It becomes challenging to establish a standardized approach without considering these factors.

Similarly, expecting a teenager to accurately assess what constitutes "overeating" can be problematic. Many active and athletic adolescents have higher caloric needs and may eat frequently to support their growth and physical activities. Additionally, the period of adolescence often includes growth spurts, which can naturally lead to increased appetite and food consumption. If you are keeping score you are now realizing how many teens can now “screen” positive fro depression.

Question #6 asks “Feeling bad about yourself- or feeling like you are a failure, or that you have let yourself or your family down”. Ughh… where do I start? First, which one is it? Feeling bad about yourself, like a failure or letting people down? So are you telling me that simply feeling bad about yourself is indicative of clinical depression? There is nothing more normal than feeling bad about yourself during adolescence. It’s a time period characterized by dramatic shifts in self confidence and pervasive self consciousness. A simple blemish or insecurity about a hair cut could lead a teen to respond to this question with a 3. If you are keeping score we now have a large portion of teenagers screening positively for severe depression for… being a teenager.

Question #7 attempts to assess trouble concentrating and refers broadly to tasks that traditionally are reported by teens as boring such as school work or reading. For some odd reason they lump in “watching tv”. In this modern technological age we now observe a large majority of teenagers struggling to attend to non stimulating or “boring” tasks like homework or reading. This questions is again trying to “medicalize” normal and consider it a “symptom” of depression when it indeed is not. Even if a child is struggling to concentrate on school work it by no means indicates the presence of a mood disorder.

Question #8 is rather perplexing as it presents behaviors that are extreme dialectical opposites, neither of which necessarily indicates depression. It is crucial to emphasize that when constructing any screening measure, the question should be clear and accurately evaluate symptoms specific to the condition in question. For instance, if assessing poison ivy, it would be important to inquire about the presence of a "visible rash" or if the person's "skin itches." In these cases, the aim is to narrow down the symptoms. However, when attempting to assess clinical depression, the idea of moving slowly or feeling restless would not typically rank among the top nine questions to ask.

Question #9 is the one question that is clinically meaningful and a potential indicator of serious problem requiring attention. Obviously, the administration of a screening measure is not required to ask this question if there is sufficient evidence of emotional or behavioral difficulties. The previous 8 questions are meaningless and will inaccurately label millions of teenagers with a mood disorder as unsuspecting medical professionals assume the PHQ-9 A is a valid screening measure for adolescent depression.

Who Funds the American Academy of Pediatrics?

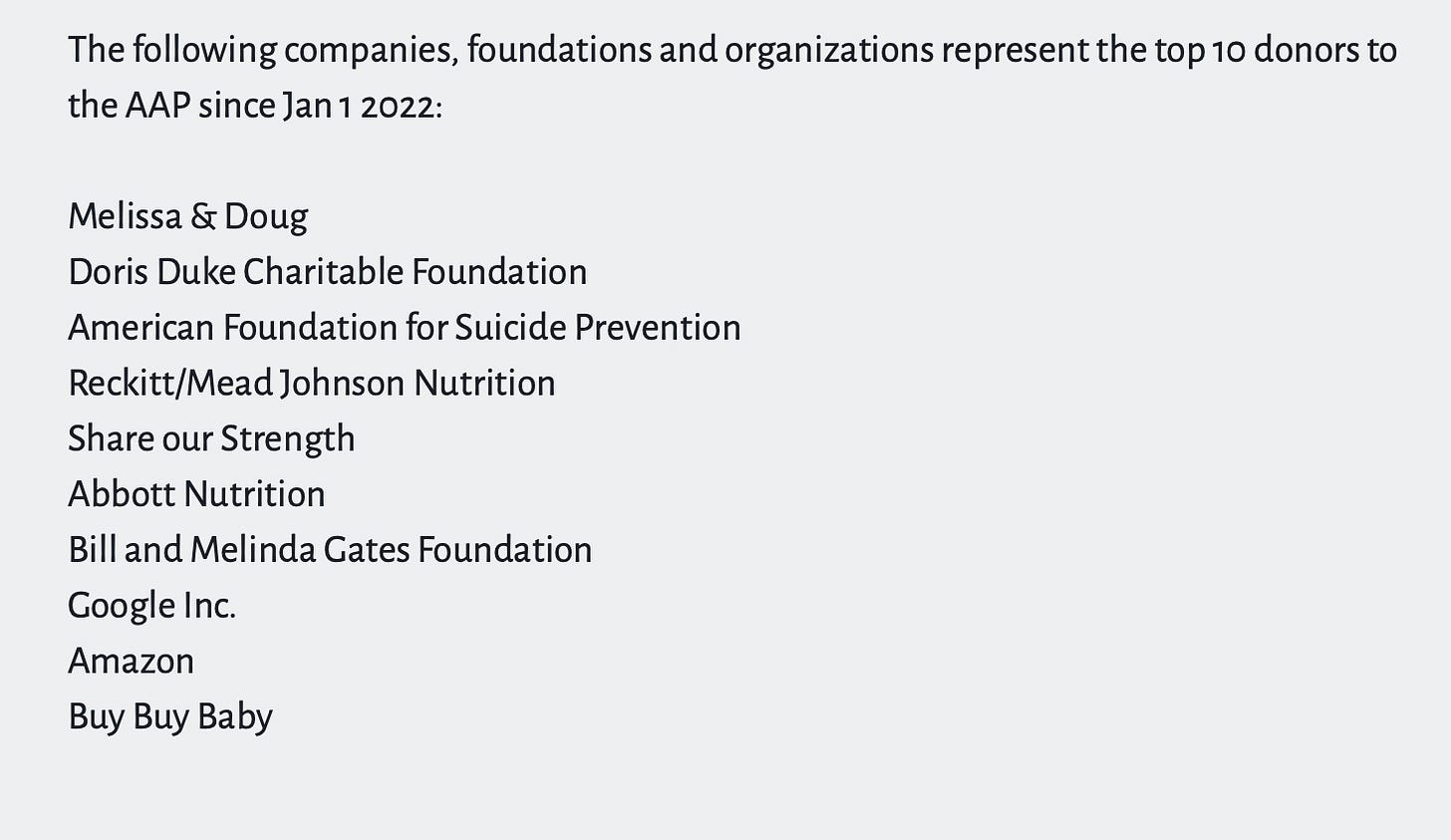

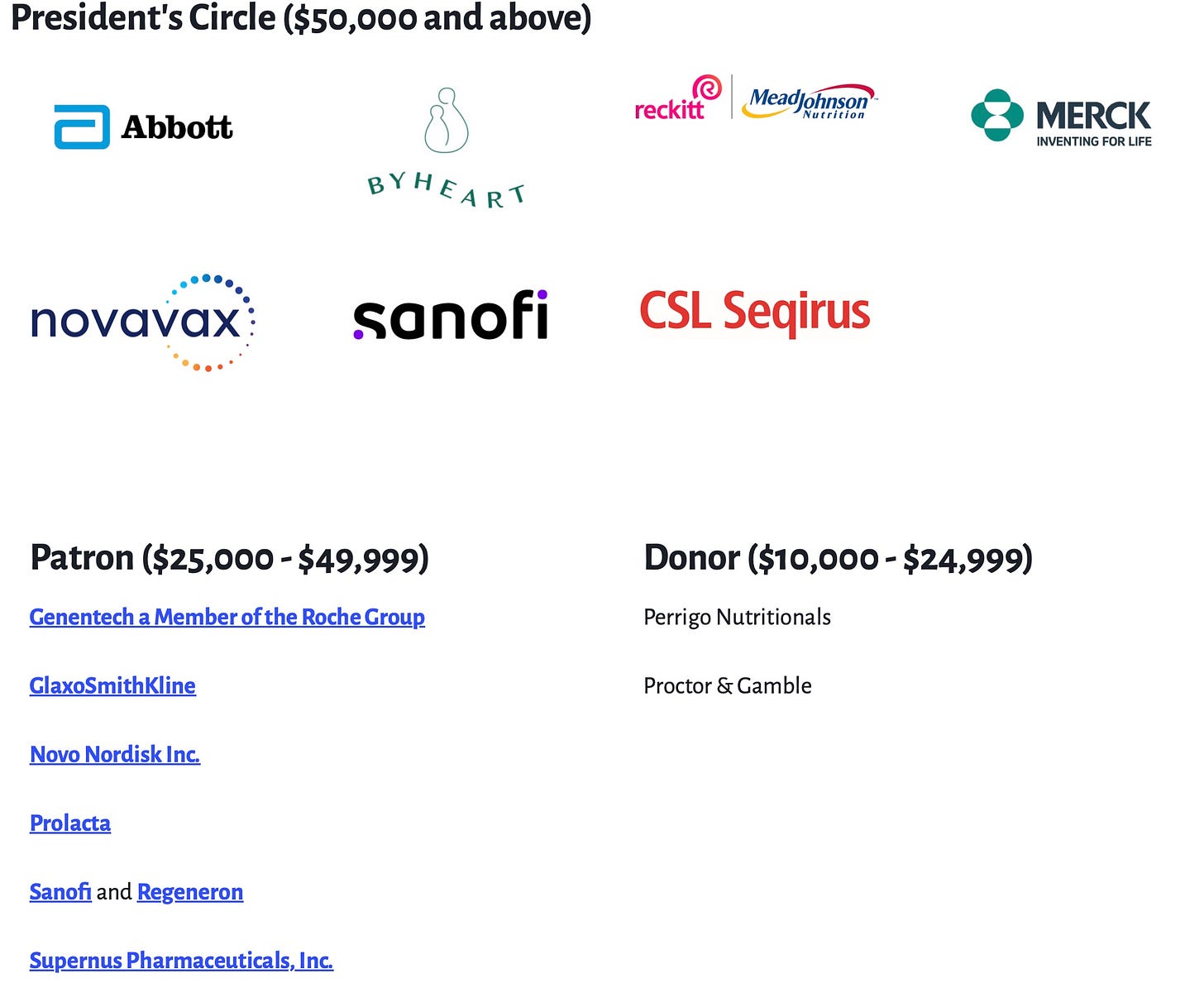

If you're curious about the potential reasons behind the American Academy of Pediatrics' inclination to amplify the number of children identified as depressed, as well as their willingness to misrepresent scientific literature by overestimating the effectiveness of antidepressant drugs and downplaying their potential risks, it's worth examining their major donors.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention receives 63% of its funding from industry. The major donors include: Pfizer, Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Mallinckrodt pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb and other pharmaceutical companies. If you examine the top 10 list of donors (unknown amount of funding) these other companies, foundations and organizations have major ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

The organizations that directly fund the American Academy of Pediatrics as listed on their website also include pharmaceutical companies, biotechnology and nutrition that profit off the Academy’s guidelines. The American Academy of Pediatrics would cease to exist without these funding resources and now they essentially control the flow of information to pediatricians through academic journals, conferences and clinical guidelines.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, AAP supported the widespread use of mask mandates and has resisted efforts to repeal them, even as COVID-19 cases declined dramatically in the United States. The organization has also supported the mass vaccination of children against COVID-19, despite acknowledging that COVID-19 is rarely a serious concern for children. This is not a science organizations. This is a political organizations with funding ties to the pharmaceutical industry. They have developed the guidelines that are falsely communicated as “Best Available Evidence”. This is frightening and we must resist

What YOU can do

If you feel that your child is being subjected to an inappropriate assessment measure for depression or being evaluated in a medical care center that may not fully understand or treat child emotional disorders, there are several steps you can take to address the situation:

Communicate with your pediatrician: Schedule a meeting with your child's pediatrician and express your concerns. Explain why you believe the assessment measure or medical care center is not suitable for your child's emotional needs. Provide them with information about the limitations of the PHQ-9 and other screening measures. Request a thorough evaluation or seek their assistance in finding a specialist who can provide appropriate care.

Seek second opinions: If you are not satisfied with your pediatrician's response or feel that your concerns are not being addressed, it may be beneficial to seek a second opinion from another healthcare professional. A medical doctor practicing functional medicine, child psychiatrist who works outside the drug model, or a child psychologist could provide a different perspective and offer alternative recommendations for evaluation and treatment.

Research mental health specialists: Take the initiative to research mental health specialists who specialize in child emotional disorders. Look for professionals who have expertise in assessing and treating children's emotional and behavioral health without relying solely on medication. Consider seeking referrals from trusted sources such as friends, family, or other healthcare professionals.

Advocate for your child: Be an active advocate for your child's well-being. Assertively communicate your concerns and preferences to healthcare professionals involved in your child's care. Ask questions, request information, and discuss alternatives to medication if you have reservations. It's important to ensure that your child receives appropriate and comprehensive care that aligns with your values and beliefs.

P.S. A heartfelt thank you to all my subscribers! While I offer all my articles for free, your support through donations would be greatly appreciated. Your generosity helps me continue delivering valuable content. Thank you for being a part of this incredible community! If you are interested in more thought provoking conversations please subscribe and download the Radically Genuine Podcast with Dr. Roger McFillin.

Well put! I think you will have a very hard time finding a pediatrician who doesn’t at least give out those questionnaires, since we get in trouble if we *don’t* do so, but it’s very important to find a pediatrician who hasn’t been co-opted by the pharma model of mental health. May I ask, regarding your action items, can you please point me to a resource for finding trustworthy counselors/psychiatrists? It is very very hard to get into any mental health provider in our area and I’m afraid some of them are all in with the AAP kind of approach.

AAP Delenda Est!

More here on vetting your pediatrician:

https://thefederalist.com/2023/04/28/prescription-for-parents-vet-your-childs-doctors-they-no-longer-deserve-your-trust/

And here on mental health perspectives:

https://gaty.substack.com/p/the-good-portion-a-warning-to-parents

You doctors of the few-and-far-between ("by design" ~ ! ~ perhaps my favourite words of yours in the above, because the sheer BAD FAITH involved in all of this is seldom named as such ~ such true doctors deserving of the designation as yourself and Dr. Gaty, are BY DESIGN no longer merely on the endangered list, but on the brink of extinction ... TPTB have many, many ways of bringing about their will, and cannot be expected to stop) ~ *you* are immeasurably precious to all of us. Thank you for your courage and your will to resist, even if you throw in the towel tomorrow. No one is superhuman. It is thanks to those like yourselves that we are not yet even more "transhuman" than we are thus far (and let us not forget that all those who've been vaccinated with patented materials are, BY LAW, now ownable as property. I, for one, am hoping not to live to see the time at which "the authorities" decide to put that little-known law into effect). May you remain safe.