Manufacturing Bipolar Disorder

How a once rare condition is misdiagnosed and harming millions.

Pause for a moment and ponder what images flash through your mind at the mention of someone who is "bipolar." If you're being honest, you might conjure up the notion of “instability”. Perhaps you envision the rollercoaster of extreme mood swings. Picture someone in the throes of a manic episode: hyperactive, possibly delusional, chatterbox, sleepless nights, and impulsive actions. Or on the flip side, imagine them sunk in profound depression, a stark contrast to the lively and vibrant individual you once knew.

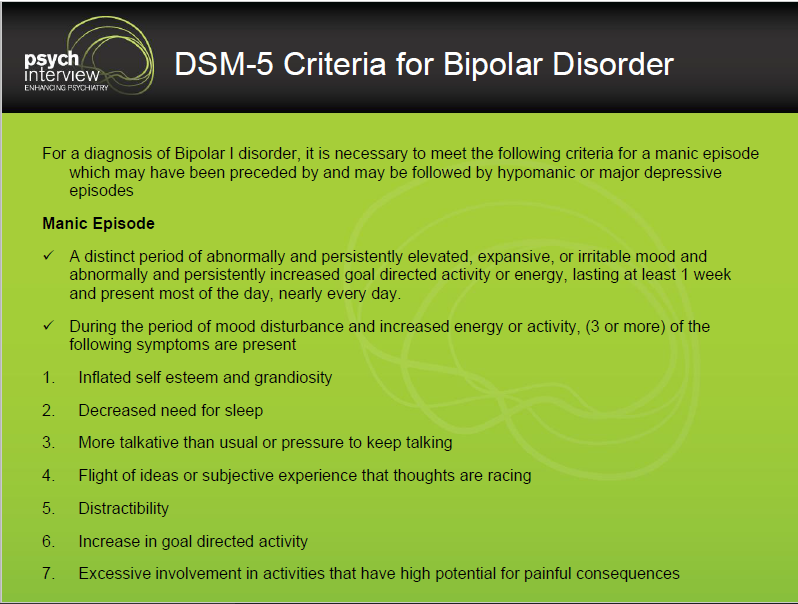

The classic perception of bipolar disorder aligns with what was once known as Manic Depressive Illness, now termed Bipolar I. According to the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), a diagnosis of Bipolar I disorder necessitates experiencing a manic episode. A manic episode is defined as a stretch of time characterized by significantly elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, alongside markedly increased goal-directed activity or energy. This state must persist for at least one week, dominating most of the day, nearly every day.

How Easy Is It To Meet Criteria For Mania Now?

Upon closer examination of the criteria outlined above, it becomes apparent that meeting the threshold for diagnosis requires experiencing just three or more of the listed symptoms. When you consider the array of seven potential symptoms, one glaring realization emerges: It's surprisingly easy to fulfill the criteria, and there's a significant risk of misinterpretation if not viewed within the appropriate context.

Take distractibility, for instance. It's listed as a symptom of manic disorder, yet it's a common trait of umm… being a human. Similarly, experiencing a decreased need for sleep over a week is something many of us have encountered, especially during periods of excitement or productivity. Not out of the ordinary for many people at certain points in their life. In fact, new mothers often report a decreased need for sleep.

Increased goal-directed activity? That’s quite vague and most people still don’t know what that actually means and is again open up for misrepresentation. That's a hallmark of meeting deadlines or being deeply engrossed in a project. It could also represent a period of increased motivation.

Just like that, we could easily tick off three symptoms. This highlights how these criteria might apply broadly to everyday experiences, potentially leading to misinterpretation without careful consideration of context. Is this purposeful? Who benefits with more people being labeled “bipolar”?

Psychiatric disorders, when reduced to categorical diagnoses based on symptom checklists, can indeed be problematic. Using such a simplistic approach risks mislabeling normal human behavior as symptoms of a severe mental illness. This approach is crude, invalid, and often misleading. It's like trying to fit the complexity of the human experience into rigid boxes, disregarding the nuances and context that shape our thoughts, moods, and behaviors.

Certainly, some individuals may experience manic episodes necessitating emergency medical attention, validating the historical recognition of manic depressive disorder as a genuine condition. However, it's crucial for ethical clinicians to thoroughly assess the disruptive and impairing nature of these behaviors. For instance, were they characterized by severe impulsivity or recklessness leading to life-altering consequences? In my experience, this isn't often the case. Instead, diagnoses are sometimes hastily assigned, even within brief clinical encounters or during acute hospital stays amidst life crises. It's also noteworthy that such severe episodes have historically been infrequent, and I would contend that they remain relatively rare even today.

Bipolar I Disorder Is Historically Rare

The research detailed in the seminal book "Anatomy of an Epidemic" by Robert Whitaker sheds light on historical trends in bipolar disorder. In 1955, there were approximately 12,750 hospitalizations for bipolar illness, indicating a disability rate of 1 in every 13,000 people. Surprisingly, outcomes before the widespread use of “medication” were surpisingly positive. Studies showed that 50% of patients in New York hospitals never experienced a second manic episode, and only 20% had three or more. Bipolar disorder was not considered a lifelong chronic illness during this era.

Moreover, research from Johns Hopkins Medical School in 1929 revealed that the majority of individuals diagnosed with manic depressive illness typically recovered within one year, with fewer than 1% requiring prolonged hospitalization. During the pre-drug era, a robust body of research indicated that 85% of those diagnosed experienced "social recovery," returning to their previous work roles, getting married, and living independently in their own homes. This information is highlighted in Washington University Professor George Winokur's 1969 book, "Manic Depressive Illness."

“there was no basis to consider that manic depressive psychosis permanently affected those who suffered from it. In this way it is, of course, different from schizophrenia.”

George Winokur, MD -1969

As previously mentioned, in 1955, approximately 1 in every 13,000 people were disabled with manic depressive illness. However, according to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), as of now, about 4.4% of all U.S. adults will experience symptoms of bipolar disorder. This translates to roughly 11 million adults, or almost 1 out of every 22 people. A 2022 long-term prospective study found that about half of patients with type I or II bipolar disorder suffer from persistent work disability that leads to disability pension.

The data suggests a concerning trend: despite the widespread use of drugs to treat bipolar disorder, there are now more individuals diagnosed with the condition and more people experiencing disability from it compared to before. What has happened?

Turning Episodic Struggles Into Bipolar Disorder

Now remember, the vast majority of people receiving this diagnosis are receiving it NOT because the doctor is actually witnessing a Manic Episode but rather based on an interview in which the doctor is asking questions about their past and interpreting it as a Manic Episode. Not the most scientific approach to identifying a “disease”, especially when someone is struggling and in the presence of an authority figure.

Memory is notoriously unreliable, let alone the myriad of other reasons why a family member or romantic partner may WANT the person diagnosed with a mental illness (that’s a topic for another post). So it’s not that we can actually trust the person experienced actual mania. Decreased need for sleep? Distractibility? Increase in goal directed behavior? Again, this reflects most people. Imagine what is going through the mind of the person feeling depressed? “I must have undiagnosed bipolar disorder!”

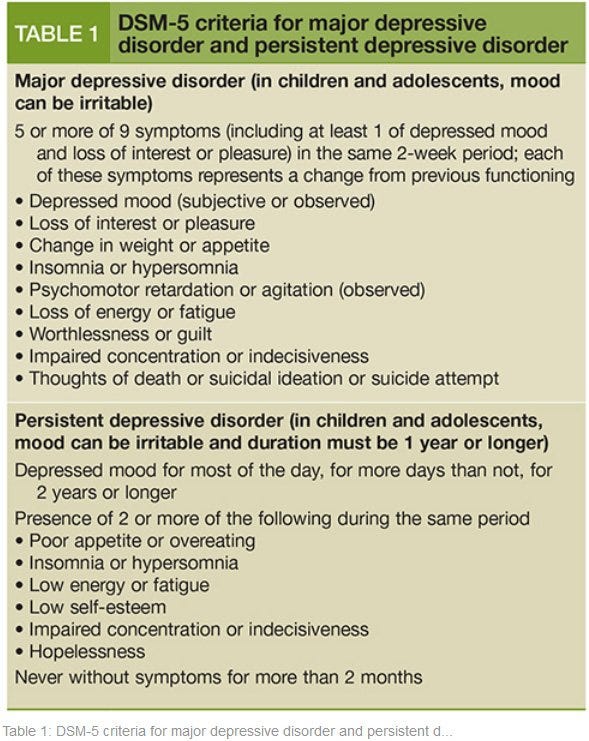

The primary reason most individuals find themselves in a psychiatrist's office or a hospital setting is often due to the presence of what psychiatrists diagnose as "Major Depressive Disorder" or some form of emotional dysregulation leading to low mood. In fact, I would argue that nearly every person could meet the criteria for major depressive disorder at some point in their life, if they reported it to a doctor. Let's take a closer look at the criteria.

Within just a short two-week span, regardless of context, individuals who experience fatigue, sleep disturbances, loss of pleasure, low mood, and changes in appetite, meet the criteria for “major depressive disorder”. However, the interpretation of these reactions can vary greatly depending on who you're speaking with. They can be viewed as normal responses to stress or adverse events, or they can be framed as symptoms of a psychiatric disease.

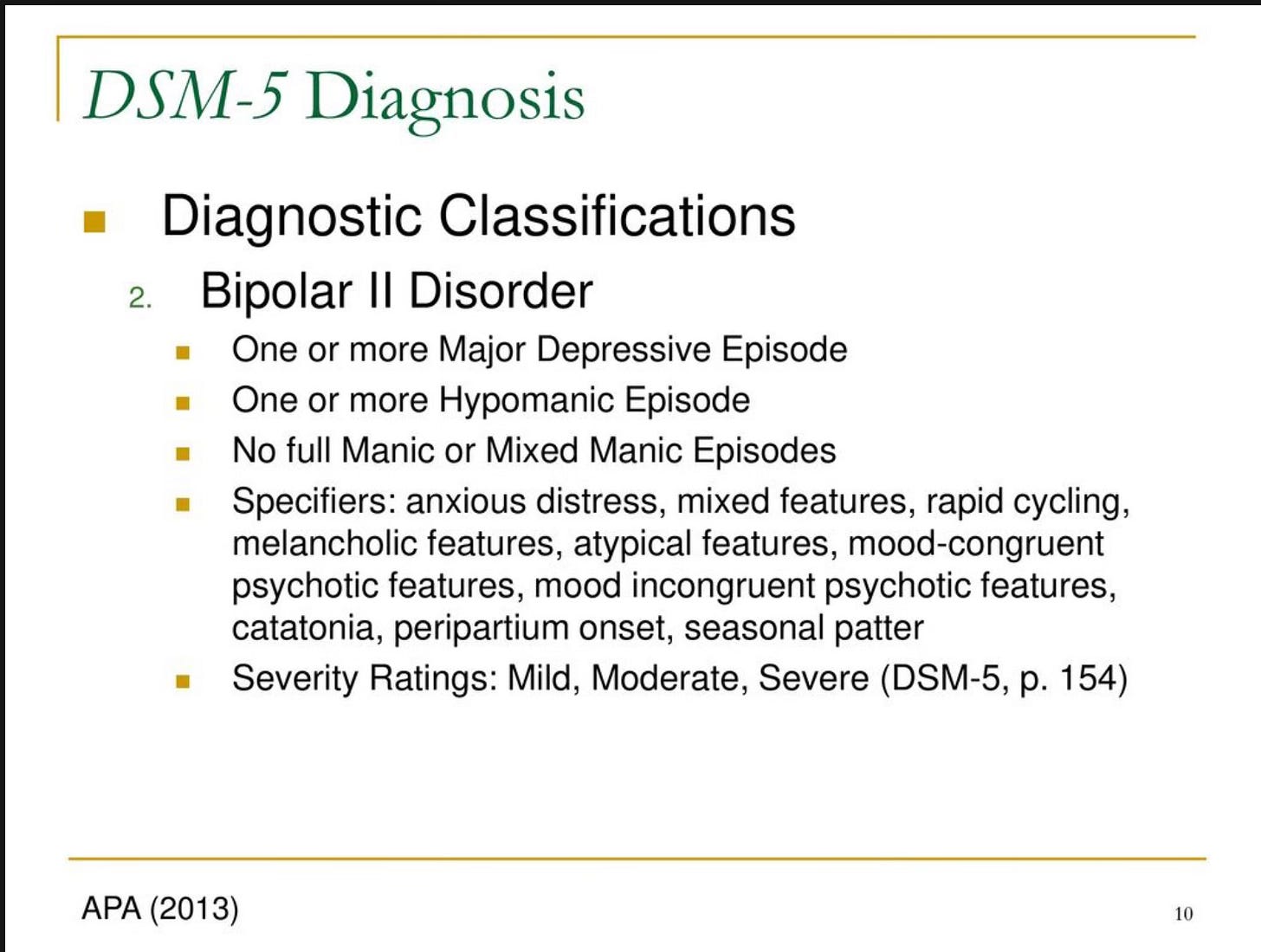

When diagnosing Bipolar I disorder, mental health professionals no longer necessarily require the presence of a major depressive episode. Instead, they can utilize the term "hypomania" to encompass various mood dysregulations within the spectrum of bipolar disorder. This broadening of criteria has led to an increase in the number of individuals meeting the diagnostic threshold, effectively expanding the prevalence of what was once considered a rare diagnosis.

What Is Hypomania and Bipolar II Disorder?

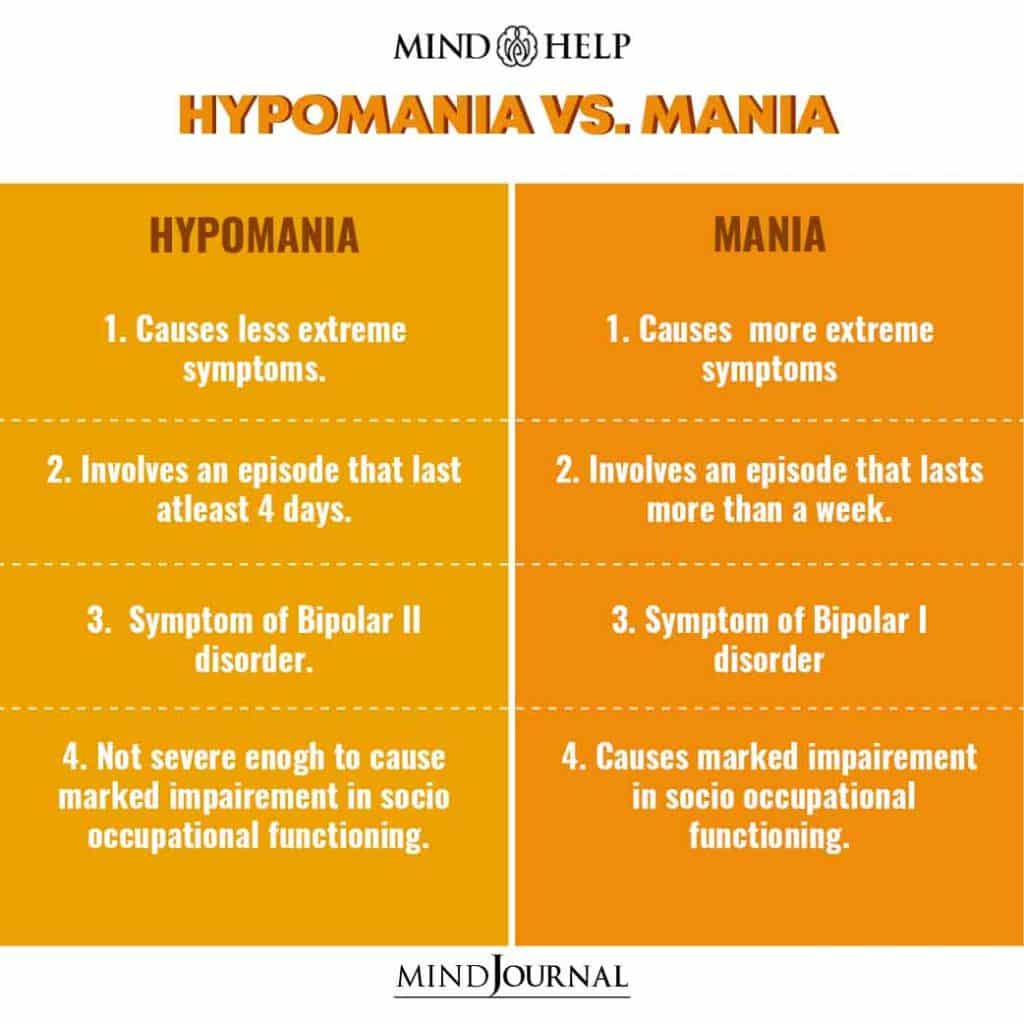

Hypomania is a bit of a running joke for those who are critical of psychiatry’s assault on normal. I have heard clinician’s refer to it as “bipolar light”. Hypomania as a core feature has lead to the astronomical rise in diagnoses of bipolar with a new category, Bipolar II.

Until 30 years ago, bipolar II disorder was the Pinocchio of psychiatric disorders-long recognized and referred to- but not a “real disorder”. Finally, in 1994, bipolar II disorder was finally given formal recognition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association 1994). This recognition has continued in all subsequent DSMs with notably little modification of its definition. Below are the criteria.

You'll notice that to receive a diagnosis of Bipolar II disorder, all that's required is a history of one Major Depressive Disorder episode (which is nearly ubiquitous) and the presence of "hypomania." But what exactly is hypomania? Well, it's tricky to pin down. Essentially, it's a milder version of "mania" with a lower threshold of just four days. Confusing, right? Let me break it down: if someone feels unusually irritable, a bit more upbeat, slightly more distractible, or struggles a bit more with falling asleep, any uninformed mental health professional could slap them with a Bipolar II diagnosis. I'm not kidding; this is serious.

What I'm witnessing is a staggering surge in bipolar diagnoses, largely driven by the Bipolar II designation. Most people, including patients themselves, often don't grasp the distinction; they simply believe they have bipolar disorder. And how do you treat bipolar II disorder? Well, the approach is typically identical to treating Bipolar I disorder: drugs upon drugs. It's yet another gateway into the mental health system, often leading to chronic reliance on medication and perpetuating the cycle of mental illness.

I've seen acute trauma victims, individuals with PTSD, teenagers, and countless others labeled as bipolar disorder, often when their presentation reflects typical mood dysregulation. Go into a hospital and leave with bipolar disorder. Once stamped with that diagnosis, it's rare to shed that label within the sick care system.

Furthermore, the similarities to bipolar disorder can be strikingly induced by side effects of widely prescribed medications, substance abuse (yes, including cannabis), and undiagnosed medical issues. Shockingly, these crucial factors are seldom given due consideration before slapping on a diagnosis. It's akin to building a house of cards, and the more we cling to this unreliable, unscientific, and compromised medical system, the sicker we'll inevitably become.

We are awake.

RESIST

I’m still waking up after stopping the drugs the doctors gave me for 30 years. Once I was physically disabled ten years ago, I started to have more time to think. It had never made much sense to think of myself as bipolar. I mean, I read the texts, the scientists and researchers. And it was all so vague. Emotions squashed, then writ larger than life, distorted. I read the autobiographies and self-help books. I went for therapy. But I never got better. And I never fit in. So, I don’t belong with the Bipolar II misfits. I’ve begun to conclude that I am not the problem.

I and many generations of women in my family have been diagnosed with bipolar, manic depression. Now I am mostly off my medication but am still dealing from the withdrawals that are still causing problems. Women primarily have been the ones diagnosed with this. The mental health industry in general was created to have a place where women could be locked up for their hysteria and melancholy. It was a way for men and society to lock away those whom were different so we didn’t have to face different and so those in society did not have to look at the harm that was being systematically placed on those who did not fit the mold of what the ruling party wanted, what made them feel comfortable what made them not have to question their status quo. The idea that “I am not the problem, you are” the truth is all of us are the problem but working together we can also come up with solutions if we just learn to communicate our needs and weaknesses and and seek inspiration to think outside the box for solutions. There are times that people have to be put away from society to get away from the noise and distractions, to heal and reflect.

For me mental health hospitals and medications may have temporarily preserved my life but they are in no way a solution and sometimes have actually caused more trauma and harm in the end.

Mental health care may seem complex. However, in my experience as both a patient and a provider the relationship, communication, and learning from one another through genuine collaboration due to true listening and exceptional problem solving skills does more to heal than any other thing. This can take time, wisdom, a willingness to learn, and a desire for healing.