Albert Einstein Would Be Labeled & Drugged Today

How we transform tomorrow's brilliance into today's disorder

In the early 1990s, before smartphones became extensions of our minds and the internet reshaped human attention, I was what many would call a 'problematic' student. There was no escape into social media, no constant stream of notifications, no digital distractions to blame for my restlessness.

Under the harsh fluorescent lights of my middle and high school classrooms, my body ached for movement while my mind wandered far beyond the prescribed curriculum. The rigid structure of traditional education – with its emphasis on rote memorization and unquestioning acceptance of authority – felt like an ill-fitting suit I was forced to wear.

When boredom struck, there were no screens to retreat into, no digital worlds to explore. Instead, my restlessness manifested in deliberately provoking teachers with challenging questions and turning to whispered conversations with classmates, not out of malice, but from a genuine frustration with the intellectual constraints of the classroom.

My persistent chatter earned me countless warnings and seat reassignments, though I'd inevitably find ways to spark discussions with whoever sat nearby. Being kicked out of class became a familiar escape from the suffocating monotony, whether for my provocative questions or for being the ringleader of yet another mid-lesson discussion group.

In today's modern world, where attention is increasingly fragmented by technology, my behavior would have likely triggered immediate concerns about attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. My restlessness, questioning nature, and difficulty conforming to classroom expectations would have been viewed not as traits to be understood and channeled, but as symptoms to be diagnosed and treated. My teachers would have welcomed the medicated compliance of a psychiatric drug.

This is progress and a ‘successful treatment’ in psychiatric care.

Yet what appeared as distraction was actually a different kind of attention – a deep, observant curiosity about human behavior and social dynamics that would later shape my understanding of psychology. While my teachers saw a student who couldn't focus on their lessons, I was intensely focused on understanding why some of my peers thrived in this environment while others wilted, how social hierarchies formed and shifted, and what made some teachers command respect while others struggled to maintain order.

My disruption was most pronounced in classrooms where teachers wielded their authority like a shield, using their position to demand respect they hadn't earned. I instinctively rebelled against those who confused compliance with learning, who filled class time with mindless worksheets and rote memorization – perhaps because even then, I recognized the profound difference between education and mere schooling. These were the classrooms where my questioning nature emerged most forcefully, not because I was incapable of attention, but because I was acutely aware of the wasted potential around me, of minds being dulled rather than awakened.

This 'distractibility' was actually laying the groundwork for my future career as a psychologist. In an era before we could Google answers or outsource our memory to devices, my wandering mind was developing a keen eye for human behavior, and my resistance to accepting information without question was forging a fierce independence of thought. Years later, these early experiences would prove invaluable in my work – I could instantly recognize the bright, restless student labeled as "disruptive" because I had been that student.

I understood viscerally why they couldn't sit still under fluorescent lights, why they challenged authority, why they sparked conversations in the midst of mindless tasks. When teachers sought my consultation for classroom management, I could translate between these two worlds, helping them see that the very students they found most challenging often possessed unique gifts that traditional education failed to recognize or nurture. My own journey from "problem student" to psychologist had equipped me with something no textbook could teach: a deep, experiential understanding of how schools could either nurture or suppress a developing mind's potential.

For me, and countless others, each classroom hour felt like an exercise in endurance, each minute stretching like taffy as my body and mind rebelled against the artificial constraints of desk-bound learning. Under buzzing fluorescent lights, trapped in molded plastic chairs, we were expected to suppress our body's natural rhythms and desires.

While some of my peers seemed to adapt to this unnatural stillness, I experienced it as almost physical pain – a crawling beneath my skin, an electric restlessness in my muscles, a mind racing against the plodding pace of standardized instruction. Yet this same body that teachers labeled as "hyperactive" found its natural rhythm the moment I stepped onto the athletic field, where movement, focus, and purpose merged into a seamless flow of action. In animated conversations with friends, time disappeared entirely, my supposedly "deficit" attention laser-focused when engaged in genuine discourse. The contrast was stark: in one environment, I was a problem to be fixed; in another, these same traits became strengths to be celebrated.

Yet success in public high school operated on a narrow definition: the ability to follow arbitrary rules, maintain silence despite burning questions, memorize facts without exploring their context, and dutifully complete mountains of tedious homework regardless of its educational value. This system rewarded compliance over curiosity, quiet obedience over passionate discourse. I learned that academic achievement had less to do with actual learning and more to do with mastering the art of sitting still, staying quiet, and playing by rules that seemed designed to extinguish rather than ignite intellectual fire.

Today, these very qualities – questioning authority, physical restlessness, divergent thinking, and intense curiosity about subjects beyond the curriculum – are increasingly pathologized as disorders requiring intervention. Teachers, wielding significant influence in the diagnostic process, often serve as the first to flag students for ADHD evaluation, their observations carrying heavy weight with parents and medical professionals. Yet their baseline for "normal" behavior reflects an industrial-age classroom model where silent compliance and stillness are idealized as natural, rather than questioning whether an environment demanding six hours of motionless attention might be the true pathology.

The gift of boredom and frustration that allowed my mind to wander, question, and ultimately find its true path would today be seen as a problem to be solved rather than a process to be understood. And perhaps most ironically, in an age where attention is genuinely challenged by unprecedented digital distraction, we're quicker to diagnose the child who can't sit still than to question whether it's natural for any child to do so.

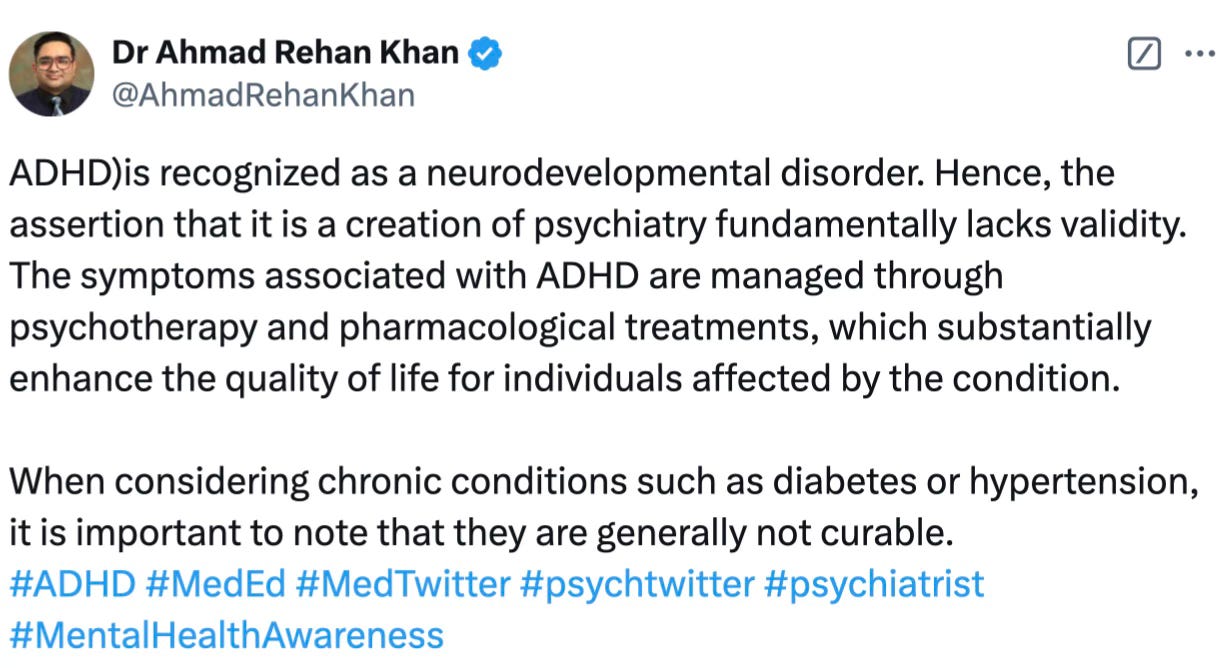

ADHD Exists Because We Say So

This tweet exemplifies the fundamental problem with psychiatric diagnostic frameworks - it begins with a conclusion and works backward to justify it. Let's dissect the logical fallacies and questionable assertions:

First, stating that ADHD "is recognized as a neurodevelopmental disorder" is a perfect example of circular reasoning. The argument essentially says "it's real because we recognize it as real." This is particularly problematic because unlike diabetes or hypertension, which can be objectively measured through blood sugar levels or blood pressure readings, ADHD has no biological markers or objective diagnostic tests. It's diagnosed purely through behavioral observations and subjective reporting of symptoms.

The comparison to diabetes and hypertension is especially misleading. These conditions have clear physiological mechanisms, measurable biomarkers, and well-understood pathology. We can precisely measure blood sugar levels in diabetes. We can quantify blood pressure in hypertension. But what exactly are we measuring in ADHD? The diagnosis rests entirely on subjective behavioral criteria that are heavily influenced by cultural expectations, environmental contexts, and individual differences in temperament.

Moreover, the tweet's assertion that symptoms are "managed through psychotherapy and pharmacological treatments" doesn't validate the construct of ADHD as a discrete medical condition. Of course stimulant medications affect attention and behavior - they do this in everyone, not just those diagnosed with ADHD. This is fundamentally different from how insulin works in diabetes or how antihypertensive medications work in high blood pressure. These medications correct specific physiological mechanisms that we can measure and verify. In contrast, ADHD medications alter brain chemistry in ways that affect everyone, diagnosed or not.

The comparison to chronic conditions like diabetes is particularly troubling because it suggests ADHD is an inherent, lifelong disorder rather than what it often represents: a mismatch between natural human variation and rigid environmental demands. If someone struggles to maintain attention in an environment filled with artificial stimulation, processed foods, and unnatural demands on focus, is this a disorder within the person or a natural response to unnatural conditions?

The tweet's author falls into a common trap in psychiatry: confusing the reliability of a diagnostic construct with its validity. Yes, we can reliably identify patterns of behavior that we've labeled as ADHD, but this doesn't mean we've identified a discrete medical condition. It's akin to reliably identifying a cluster of symptoms we might call "modern life syndrome" without questioning whether these symptoms represent a disorder within the individual or a rational response to irrational demands.

The ‘ADHD’ Label Obscures Both Problems & Potential

The fundamental problem with the ADHD diagnosis is that it simultaneously explains everything and nothing. By attributing a cluster of behaviors to a presumed neurological condition, we create a diagnostic label that acts as a cognitive stop sign, preventing deeper investigation into both challenges and strengths. This reductionist approach fails in two critical directions: it neither helps us understand and nurture unique talents, nor does it guide us toward addressing legitimate environmental and lifestyle factors that may be creating genuine difficulties.

Consider three children exhibiting similar 'symptoms' in a classroom setting - difficulty sitting still, trouble maintaining attention on assigned tasks, and tendency toward impulsive behavior. The first child consumes a diet high in processed foods, spends hours each day on social media, and gets minimal physical activity or time in nature. The second child possesses intense curiosity, shows remarkable creativity when free to explore their interests, and demonstrates an intuitive understanding of complex systems that doesn't align with traditional educational approaches. The third child lives with chronic uncertainty and fear at home, where unpredictable abuse and neglect have taught them to remain hypervigilant, distrustful of adult authority, and ready to fight or flee at any moment. By funneling all three children into an ADHD diagnosis, we perpetuate a self-sustaining industry of evaluation, medication, and ongoing management that profits from deliberately ignoring root causes.

For the first child, the ADHD framework ensures we never seriously examine how lifestyle interventions could resolve attention issues without medication - a pattern that mirrors our broader healthcare system's approach to chronic disease. Just as we medicate children for attention problems while ignoring their processed food diets, sedentary behaviors, and technology addiction, we treat type 2 diabetes, obesity, and heart disease with increasingly expensive medications rather than addressing their shared roots in modern lifestyle patterns.

This creates two parallel and profitable industries: one managing behavior through psychostimulants, the other managing chronic illness through lifelong medication protocols. In both cases, the medical establishment positions itself as the solution while systematically ignoring its role in perpetuating the very conditions it claims to treat. Any suggestion that these issues might be prevented or reversed through lifestyle changes is dismissed as too difficult or impractical, conveniently preserving a system where both distracted children and chronically ill adults remain dependent on pharmaceutical interventions.

For the second, it creates a lifelong patient out of a child whose only real problem is mismatched learning environments. Had Albert Einstein been born in today's era, his legendary daydreaming, difficulty with traditional instruction, and tendency to question authority would likely have earned him an ADHD diagnosis and a prescription for stimulants before his tenth birthday.

Rather than recognizing these traits as hallmarks of revolutionary thinking - the very qualities that enabled him to reimagine the nature of space, time, and reality itself - our modern medical system would have labeled them as symptoms to be suppressed. The same divergent thinking patterns that led to the theory of relativity would be reduced to items on a diagnostic checklist, with pharmaceutical intervention prescribed to make him a more compliant student.

But for the third child, the diagnosis becomes something more perverse - a stark demonstration of psychiatric hubris and the dangerous limitations of medical training. I witness this routinely in clinical practice: a psychiatrist, after a 15-minute evaluation, confidently labels a clearly traumatized child with ADHD, seemingly blind to or uninterested in the chaos and violence marking their home life. The sheer audacity of reducing complex trauma responses to a simple neurological disorder would be almost comical if it weren't so damaging.

This cursory diagnostic process, taught in medical schools and reinforced through years of practice, creates a kind of institutional blindness where even obvious signs of abuse and neglect are reframed as symptoms of a brain disorder. The ADHD label then spawns an endless cycle of appointments, prescriptions, therapy sessions, and educational accommodations, all while leaving the underlying causes of distress completely untouched.

The medical establishment's comparison of ADHD to diabetes isn't just scientifically dubious - it reveals a profound ignorance of human suffering and adaptation that delegitimizes psychiatry's claims to medical authority. Each diagnosed child becomes not only a reliable source of revenue for an interconnected network of professionals, pharmaceutical companies, and healthcare systems, but also a victim of institutional gaslighting where their very real trauma is systematically denied and rewritten as a chemical imbalance.

In my practice, I've learned that our first duty is often to protect people from their diagnoses, to help them understand how their so-called symptoms might be their best attempts at surviving an impossible situation.

A Disorder At One Time… Becomes a Gift Later

Throughout my early career, I encountered countless boys whose ADHD diagnoses told only a fraction of their story - and perhaps the wrong fraction entirely. These were boys who couldn't sit still in fluorescent-lit classrooms but could maintain laser focus during baseball practice, who struggled with algebra but could instinctively calculate complex spatial relationships while skateboarding. Many went on to become skilled carpenters, electricians, and mechanics - their supposedly scattered attention revealing itself as an ability to track multiple aspects of a complex project simultaneously.

Photo of an ‘ADHD’ diagnosed boy in action.

Others found their calling in military service, where their heightened alertness and quick responsiveness - traits that had earned them reprimands in school - became vital survival skills and leadership qualities. The very characteristics that the educational system had labeled as deficits - physical restlessness, need for immediate feedback, preference for hands-on learning, heightened awareness of their environment - became assets in professions demanding physical precision, spatial awareness, and rapid decision-making.

What's most tragic is that many of these young men carried the weight of their early diagnosis into adulthood, still believing something was "wrong" with them even as they excelled in their chosen fields. They had been taught to see their natural inclinations as symptoms rather than strengths, their energy as disorder rather than drive, their different way of engaging with the world as dysfunction rather than diversity.

Robert Greene's book 'Mastery' illuminates a fascinating paradox in how we view human traits and behaviors. What society labels as a disorder in one context often emerges as a profound gift in another, or proves essential to achieving mastery later in life. Greene's extensive research into the lives of masters across history reveals a pattern: many of these individuals possessed traits that would likely be pathologized in today's educational system.

The very nature of intense focus in one area of life often creates an apparent paradox that our medical system misinterprets as dysfunction. When a mind is deeply engaged with a compelling problem or interest, it necessarily dims its awareness of other stimuli - not due to an attention deficit, but rather as a manifestation of attention's natural selectivity.

This is how consciousness works: to focus deeply on anything requires the ability to filter out other inputs, to create a kind of cognitive tunnel vision that enables deep understanding at the expense of broader awareness. My own academic experience illustrates this perfectly: what appeared as inattention in geometry class masked a different kind of deep engagement - not with the sequential steps of proofs on the chalkboard, but with fundamental questions about human nature and society unfolding in the classroom around me.

While the teacher saw a student missing basic mathematical steps, my mind was actually performing sophisticated analysis of social hierarchies, power dynamics, and human behavior. The same selective attention that made me appear "scattered" in traditional academic metrics was actually enabling a deep understanding of human psychology that would later become my life's work. This wasn't a failure of attention but rather attention working exactly as it should - focusing intently on what my developing mind recognized, perhaps unconsciously, as essential to my future path, even as it appeared to be a deficit within the narrow confines of traditional education.

The tragedy of our current approach extends in two critical directions. While we rush to pathologize natural variations in attention and engagement - medicating the future craftsman's physical intelligence, the budding artist's sensory sensitivity, or the emerging leader's questioning mind - we simultaneously fail to recognize when children are genuinely struggling with environmental toxins, processed food diets, technological addiction, trauma, or abuse. By reducing all attention and behavioral differences to a single diagnosis requiring pharmaceutical intervention, we commit a dual betrayal: suppressing unique gifts and talents while leaving real suffering unaddressed.

The ADHD label becomes both a straightjacket for human potential and a blindfold that prevents us from seeing genuine problems that demand intervention. Perhaps the real disorder lies not in these children's brains, but in a society that would rather medicate its youth into compliance than either celebrate their differences or address the true sources of their struggles.

Another excellent piece Roger. I’ve worked in the industry for many years now and find it deeply concerning, just how unthinking and compliant so many people working in services are.

I wonder if people in certain sectors have tendencies to experience stronger cognitive biases cementing beliefs in place? Having said that I think its also mostly down to ignorance about the history of their own and related professions and the ongoing debates. In addition many have only worked in one service without much diversity of experience.

The bias, ignorance and limited experience combined acts as a sort of blinding agent, repelling any chance of learning and change and helping to cement the current toxic zeitgeist in place.

There is also something strangely alluring and powerful about psychiatric diagnosis and especially in applying them to others, that many in the therapy industry seem to really love. Perhaps its the illusion of professionalism or certainty or both?

I’ve tried mostly in vein over the years to share basic information about all of this, but very few are open to it. This is all the more disturbing given most of these people on a daily basis will be encouraging their own clients to look for the evidence, do their homework and question their thoughts, beliefs and assumptions, but are completely unable to do so themselves.

If its made it all the way to the lofty heights of a guideline its beyond question, right?

I saw a brief presentation by Brian Klass recently and he mentioned some ideas from self organised criticality and the sandpile model - we’ve created systems like sandpiles, more and more sand keeps getting added until the system enters a phase of being on ‘the edge of chaos’ whereby one more grain can cause collapses.

This felt to me like the mental ill health industry - its feasting on its own ignorant self interest and eventually will likely collapse in on itself and this phase I’ll call the Alice in Wonderland phase when Alice is talking to the cat:

“But I don’t want to go among mad people," Alice remarked.

"Oh, you can’t help that," said the Cat: "we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad."

"How do you know I’m mad?" said Alice.

"You must be," said the Cat, "or you wouldn’t have come here.”

I would love to see some interviews with some of these folks - the authors of the PTMF

https://www.bps.org.uk/member-networks/division-clinical-psychology/power-threat-meaning-framework

Sami Timimi psychiatrist in an award winning children's team in the NHS and author of several books such as Insane Medicine and he’s got a new book coming out soon -

https://www.madinamerica.com/insane-medicine/ and this is great

https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatry-social-construction-sami-timimi

Lucy Johnstone author of the excellent straight talking introduction to psychiatric diagnosis 2nd edition and founder of drop the disorder and much more

https://www.adisorder4everyone.com/ and this is very useful

https://www.madinamerica.com/neurodiversity-series/

This book is also very good - ADHD is not an illness and Ritalin is not a cure: a comprehensive rebuttal off the (alleged) scientific consensus. Yaakov Ophir

Keep up the good work its so needed.

Absolutely fantastic article. ADD/ADHD are simply terms that are used to label children as problematic and anyone in this world who is "problematic" is conditioned to think popping copious amounts of pharmaceuticals is the answer. Kids who exhibit the traits of ADD/ADHD are not built for the society that we live in. Children should be outside running around, getting into mischief, using their imaginations, not stuck in what can only be described as a prison and that is school. I was diagnosed with ADD, not ADHD, because of my lack of attention to stuff I did not care to learn or do. If I am interested in something I will get very involved in doing/learning it, if I am not there is nothing on this earth that will make me do so, not even large amounts of adderall will get me motivated. It's not that I'm slow or stupid, I read hundreds of novels a year and can be considered to be an autodidact, it's that my brain is not wired to give a shit about something that bores the ever loving hell out of me. Give me a book on the fall of Rome and I'll read it in a day, give me a book on systematic racism and my eyes will glaze over and I will never pick it up. In a normal society people like me would be allowed to study the topics we want to learn about and not be forced to conform to the lowest common denominators of society.